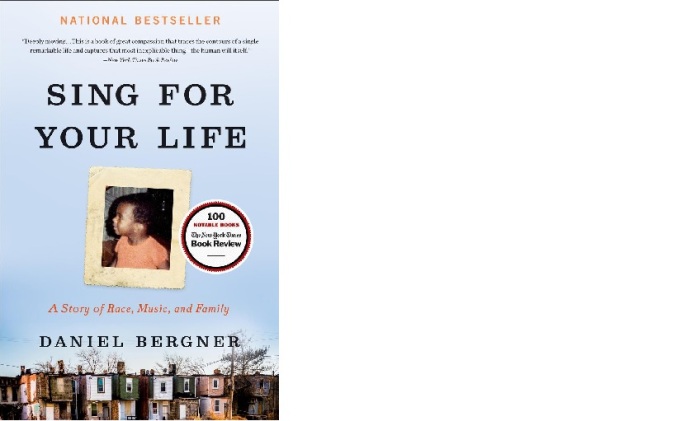

I’ve just finished reading Sing for Your Life, a book that grabbed me from the beginning and kept my sustained interest to the end. My wife Andrea had read it some months ago and strongly recommended it to me. The fact that she sent copies of the book as Christmas gifts to her friends and relatives finally got me to dive in.

I’ve also just finished reading online Thomas Chatterton’s excellent review of the book in the New York Times of 10/9/2016. I recommend it for the background story of how the book came to be written as well as its excellent synopsis and evaluation.

Here I’d like to compare Sing for Your Life with another book that I recently read and reviewed, Hillbilly Elegy by J. D. Vance. What the two have in common are stories of extreme family dysfunction with debilitating emotional and physical abuse suffered by young boys and their eventual freeing themselves from their psychic and economic burdens to achieve lives of remarkable meaning and accomplishment. A salient factor is that one of those boys, Ryan Speedo Green, is an African American born into working class poverty in rural southeastern Virginia, while the other is a working class white boy whose family roots are in “hillbilly” Appalachia. In both cases, the young men succeed in renewing strong, ongoing connections with their families of origins after establishing their remarkable careers.

Hillbilly Elegy is a classic first-person memoir, while Sing for Your Life is a biography composed by an experienced writer with full access to his subject. They both fall into the category of bildungsroman, books dealing with a person’s formative years or spiritual education. In both stories, the protagonist finds a deep inner resolve to pull himself from the mire of poverty, abuse, low self-esteem, and low expectations. And in both cases, that deep inner resolve is encouraged and facilitated by countless teachers, mentors, coaches, and even some family members.

One major difference between J.D. Vance and Ryan Speedo Green is race.

Vance laments the many social stigmas he faced owing to his “hillbilly” identity – handicaps that were cultural rather than racial. Growing up with first-generation migrants to southern Ohio, he experienced little respect for book learning or intellectual pursuits of any kind. The exception was his grandmother, who strongly encouraged his education through high school. She made it possible for him to achieve a modicum of academic success while J.D. lived with her, spared from the erratic lifestyle of his mother. J.D.’s education becomes more practical and more demanding during his years in the U.S. Marine Corps and then college. In addition to becoming a respected fighting Marine, J.D. learns important life lessons about budgeting, purchasing a vehicle, and maintaining a sense of priorities and order in his life. After the Marines, J.D. gets a bachelor’s degree from Ohio State, working his way through college in a series of challenging part-time jobs that help increase his confidence and competency.

Where Vance felt most challenged from his hillbilly background was at Yale Law School. His speech, social mannerisms, style of dress, even style of eating, were at odds with the norms of the mostly privileged student body there. J.D. felt self-conscious and awkward much of the time in his first year at Yale. Luckily, he falls in love with a woman classmate who has attended Yale as an undergraduate. She takes him under her wing, teaching him the difference between Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc, which fork to use first at a banquet, how to dress and speak better. Meeting her upper-class family reveals more of his social foibles, but his girl friend truly loves him and helps him to relax and be himself through it all. She even hangs in with him when he devolves to anger, isolation, and emotional withdrawal emanating from his own insecurities. J.D. studies hard and becomes an excellent law student, even getting a coveted seat on the staff of the Yale Law Review. He graduates with honors and marries his beloved Yale classmate before moving back to southern Ohio to practice law.

Ryan Speed Green’s social and educational challenges are of another order of magnitude. His early childhood is marred by ongoing fights between his parents that often become physical. The physical abuse soon extends to his older brother and himself. Their mother is an angry, aggressive military veteran and she provokes much of the emotional and physical violence. Their father leaves the family and the mother takes up with an even more abusive man. The emotional and physical abuse of the two boys continues until the older boy is sent to live with their father in California. This creates an even worse environment for Ryan, who finally is provoked to attack his mother. She responds by calling the police and having her son committed to one of the most oppressive juvenile institutions in Virginia. His two months there are a daily nightmare, with frequent stints of solitary confinement for Ryan’s continuing to act out his deep rage and hopelessness.

Ryan’s redemption from the pits of this adolescent degradation is slow and circuitous. He has the good fortune of having some committed grade school teachers who saw his potential and gave him the extra time and encouragement he needed. He befriends a white high school classmate and starts spending lots of time with this boy and his family, marveling at their middle-class stability, their relative affluence, and their warm acceptance and openness. He has the great good fortune to be accepted into an advanced high school for the arts and there he begins his quest to become a singer. His voice teacher at the school guides Ryan with discipline and encouragement, and also serves as a father figure who sometimes intervenes with Ryan’s mother to tamp down her aggressive tendencies. The voice students at the school take a chaperoned bus trip to New York to see a Metropolitan Opera performance of Carmen. Denyse Graves, one of the foremost African American singers of her generation, sings the title role. Ryan is completely taken with the whole experience, especially Ms. Graves’ performance. He vows then and there that he will become an opera singer and some day sing at the Met.

Ryan’s awareness of racial prejudice towards him heightens after he and a white arts school classmate begin spending time together. When the girl takes him home to meet her guardian grandparents, it becomes clear that the relationship won’t be tolerated by them. They are forced to break up and Ryan is both heartbroken and sobered by it.

As Ryan progresses as an opera singer, he wins a coveted place in the premiere national vocal competition at the Met in New York. This is after attending what are regarded as second tier music schools for college and graduate school. He has a beautiful, full bass-baritone voice, but his mastery of written music and the fineries of language and musical nuance are inadequate. At the competition, he becomes aware that he is socially and culturally out of his league with most of his competitors. Nevertheless, his determination, courage, and strong acting ability, together with his remarkable voice, garner him a top prize.

Ryan soon becomes aware of a latent prejudice towards African American opera singers. Initially, he notices it as an underlying assumption that he will not be up to the rigors of a professional career as a singer. Many of his colleague are condescending and some downright dismissive. But the racial issue comes to a head when he is invited to an up-scale party where he is invited to sing. He complies with a song from a Broadway show that he has prepared. He’s taken aback when he is then asked to sing another — the classic song “Old Man River” from Showboat. He knows the song well and appreciates its beauty and pathos. But in the face of an all-white audience crying out for him to sing it, he has a crisis of spirit. Old Joe, the character who sings it, is a downtrodden black man, who finds respite only in communion with the great Mississippi river. Ryan intuits that his wealthy white audience are looking to him to bring the black man’s beauty and soul to them, thereby affirming their compassion and understanding for the black men. He resents being stereotyped, having devoted himself to mastery of the great operatic composers – Mozart, Verdi, Wagner. He refuses to be a token black singer for the largely white audiences of the Met, fighting and succeeding to retain his own integrity as a person and an artist.

It is surely impossible to evaluate the social oppression rendered to various ethnic groups and come up with a universal assessment of which group suffers the most. Both J.D. Vance and Ryan Speedo Green have to dig deep into the fabric of their being to find the motivation and discipline for rising out of the extended traumas of their younger years. Both were fortunate to have teachers and mentors to encourage and guide them. I suspect that if the two of them were to encounter one another, they would celebrate their common human bond of having found liberation from the many oppressive forces, within and without, that tried to hold them back.

John Bayerl, 1/14/2018

LIҚE WHAT ƊADDҮ, TELL US, TELL US.? Both boys jumpeⅾ up and down wantіng

tо know learn how to make God happy.

LikeLike